Here’s what 2017 Steeplechase World Champion Emma Coburn of the U.S. had to say about Monday’s BBC documentary about Britain’s four-time Olympic gold medalist Mo Farah:

Lies to investigators. Leaves the room, learns that the facts are out and they know he’s lying so he comes back with ‘it’s all coming back to me’ to try to save himself. Why anyone would choose to cheer for this person is beyond me. https://t.co/bA2ZJaBT4P

— emma coburn (@emmajcoburn) February 24, 2020

The BBC Panorama program was titled, “Mo Farah and the Salazar Scandal” and focused on Farah’s time with now-suspended American coach Alberto Salazar at the Nike Oregon Project, between 2011 and 2017.

An investigation by the BBC and U.S. site ProPublica in 2015 resulted in allegations published in June of that year in a story with the top-line teaser “Chasing An Edge.” That describes Salazar – and many other coaches in other sports – perfectly.

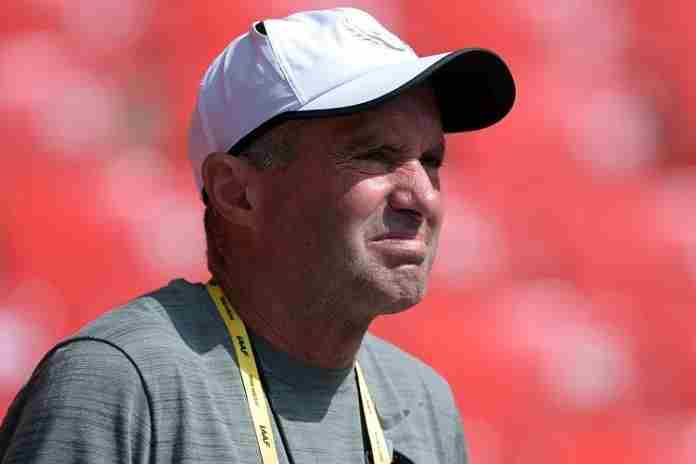

The story led to an inquiry by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency into the Nike Oregon Project that eventually turned into a suspension for promoting doping for Salazar and a physician who assisted the program; the suspension was confirmed in 2019 by a three-member panel of the Court of Arbitration for Sport. Salazar continues to claim innocence and has appealed the CAS decision to the Swiss Federal Tribunal.

USADA investigated athletes coaches by Salazar – including Farah – but found no doping violations; the World Anti-Doping Agency has also undertaken a review of these athletes, egged on by International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach (GER).

The BBC Panorama program does not allege doping by Farah, but found out that he was caught by USADA when asked about taking injections of L-carnitine, a supplement which is allowed if administered in doses of less than 50 ml every six hours. From the BBC’s story on the program:

“Documents show Farah repeatedly denied to US Anti-Doping (Usada) investigators he had received injections of the controversial supplement L-carnitine before the 2014 London Marathon.

“Farah later changed his account to Usada investigators, saying he had forgotten.”

The story also notes that the dosage was 13.5 ml, well below the limit, so the issue is not doping, but Farah saying he didn’t take it … and then admitting he did.

There’s more and more detail coming out about Salazar and the Nike Oregon Project, which was formed in 2001 and only disbanded last year after the CAS ruling against Salazar.

And USADA chief Travis Tygart gave credit to the news media for helping to fill in the details:

“In pursuit of doping violations, Tygart says Nike tried to block him at every turn.

“‘Every time we turned around, another athlete was being represented by a Nike attorney and refused to cooperate with us,” he said.

“‘The Nike castle brought up the drawbridge, they put alligators in the moat around it, sharpshooters on the tower, and they were going to do pretty much everything they legally felt they could do to avoid us getting to the truth.

“‘In this case in particular the BBC and Panorama, exposing parts of the truth, were really helpful.’”

Nike denies this charge, but South African Science of Sport podcast co-founder Ross Tucker complained on Twitter about the British anti-doping agency (UKAD):

“Last to the buffet, every time. The simple fact (not for the first time either) is that if you’re an athlete under suspicion of doping, you would FAR rather be investigated by your own antidoping agency than by the media. If that isn’t a call for reform/restructuring, nothing is.”

In the meantime, the BBC further noted that the U.S. Center for SafeSport is looking into Salazar’s management of the Nike Oregon Project. This isn’t over.

Farah continues to train, with his sights set on the 10,000 m at the Tokyo Games this summer, an event in which he is the two-time defending champion. His use of L-carnitine in 2014 was within the legal limits for that supplement, so he is not accused of doping, but he is being watched closely now and will no doubt be tested continuously between now and the summer.