/Updated/Last month’s opening day of the FIFA World Cup 2022 qualification matches in Europe’s Group G saw Norway win, as expected, at Gibraltar by 3-0 in a game that was even more lopsided than the final score.

But the story was the T-shirts worn by Norway’s players prior to the game, inscribed with the message: “Human Rights” in bold letters and “On and off the pitch” in smaller letters below.

The object of the shirts was to show support for migrant workers in Qatar, which will host the FIFA World Cup in 2022 and has built seven new stadiums for the event, primarily using construction workers from other countries. It has been reported that 37 workers directly involved with stadium construction have died, but also that since the World Cup was awarded to Qatar in 2010, there have been some 6,500 deaths among the migrant worker population, leading to heavy criticism of the Qatar government.

FIFA, the worldwide governing body for football, responded to the Norwegian incident with a statement including “FIFA believes in the freedom of speech, and in the power of football as a force for good. No disciplinary proceedings in relation to this matter will be opened by FIFA.”

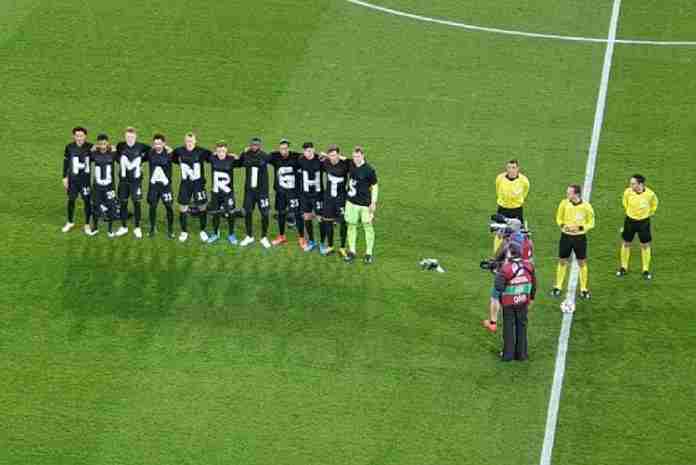

The next day, 25 March, saw the first day of matches in Europe’s Group J, including powerhouse Germany hosting Iceland at the MSV Arena in Duisburg. It was also a 3-0 final, with the Germans scoring twice in the first seven minutes. But once again, the real action came before the game.

The German team lined up for introductions and its anthem wearing black shirts that spelled out “HUMANRIGHTS” in block letters, again focused on the activities in Qatar.

FIFA’s statement was essentially the same: “FIFA believes in freedom of expression and in the power of football to drive positive change.”

Football’s Laws of the Game covers this area in Law 4:

“Equipment must not have any political, religious or personal slogans, statements or images. Players must not reveal undergarments that show political, religious, personal slogans, statements or images, or advertising other than the manufacturer’s logo. For any offence the player and/or the team will be sanctioned by the competition organiser, national football association or by FIFA.”

While shirts worn for warm-ups and not during competition could be considered a gray area, there’s no doubt that FIFA could have imposed sanctions. It didn’t and that’s worth remembering as the International Olympic Committee gets ready to receive recommendations from its Athletes’ Commission on possible changes to Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which reads:

“No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.”

A set of guidelines was issued in January 2020 by the IOC’s Athletes’ Commission, prohibiting protests on the field of play, on the victory stand, during ceremonies and in the Olympic Village. But protests were welcomed on social media, within team meetings and in interactions with news media.

In the aftermath of multiple deaths in the U.S. later last year – including George Floyd in Minneapolis on 25 May – the IOC’s Executive Board asked its Athletes’ Commission to revisit the issue and a lengthy consultation process will result in recommendations being sent back to the Executive Board this month.

As regards taking a knee or raising a fist on the victory stand, that outcome has already been telegraphed by Athletes’ Commission Chair Kirsty Coventry (ZIM) in a 10 December 2020 tweet that included:

“While the consultation is still ongoing, from what we have heard so far through the qualitative process, the majority:

● emphasise the right of free speech which is respected at the Olympic Games; and

● express support for preserving the ceremonies, the podium and the field of play.”

The U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee has said that it will not sanction its athletes for such behavior at the Games, but has held off on formal regulations on protests for the Games until the IOC has concluded its review. (The USOPC has issued guidelines on protest activity at Olympic Trials events, here.)

And U.S. athletes are considering their options; Ashleigh Johnson, the gold-medal-winning goalkeeper for the U.S. women’s water polo team at Rio in 2016 – who is Black – said at the Team USA Media Summit:

“I think that how I developed, on field protests, versus from where I started to where I am now, has gone along with how I matured as an athlete. Like, it takes a while to see your role in the grand context and it takes a while to understand how you can apply your beliefs and clarify those, and how those translate to like, what’s going on. …

“It’s really hard to grow as an athlete when you’re so focused on your career, in the pool, or on the field, and like, there’s also this expectation to bringing this voice that has so much behind it, has so much greater reach than just you.

“I think that a lot of people are now taking the time to understand where they fit in, in the context of not just their sport, not just who they are as an individual, but like within the context of the Olympic Movement, within the context of the world, and what’s going on. … I think it just takes time to see yourself in that, and to understand like where your placement is.”

But as Tokyo 2020 looms, with possible protests from U.S. athletes concerning issues at home, the spectre of the 2022 Olympic Winter Games in Beijing, China looms, and its treatment – already labeled as genocide by multiple governments, including the U.S. – of the Uyghur Muslim minority in the Xinjiang province. The Chinese government has pushed back hard against any characterization of its treatment of the Uyghurs – including movement into “re-education camps” – as improper and promises an unspecified “response” to any actions, demonstrations or protests about the issue.

In considering the future of Rule 50, the IOC now faces the question of not just whether some American athletes will raise a fist or take a knee in Tokyo this summer, but how to handle protests against the Chinese regime in 2022.

What will be tolerated? What won’t?

My own view is that athlete boycotts are the wrong answer, because when teams are missing, so is their voice, both individually and collectively. But once we get past that, other questions open:

● Will governments support their teams by sending them – this applies to all countries except the U.S. – and then show their disgust with the Chinese government by recalling their ambassadors and shunning the Games by not sending any national representatives? U.S. Senator Mitt Romney (R-Utah), who headed the 2002 Olympic Winter Games organizing committee in Salt Lake City, has eloquently expressed this view and much more in a 15 March editorial.

● It will be fascinating to see whether athletes – especially those in the U.S., whose voices have been the loudest on Rule 50 – take up the cause of the Uyghurs, whose situation appears to be even worse than for Germany’s Jews when the 1936 Olympic Games took place in Nazi-led Berlin, when the Beijing Games open next February.

● What will athletes and teams be able to do in Beijing – with IOC approval – to show their concern? Will Norwegian- or German-style T-shirts during warm-ups be accepted? What about special pins? What is national teams include a reference – by color or symbol – to the Uyghurs on their uniforms?

Interestingly, the pale-blue color used on the Uyghur flag is more-or-less already part of the Beijing 2022 logo!

● FIFA has already declared that it is willing to support at least some limited protests, and in circumstances that draw close attention from the television cameras, just prior to the start of matches. That’s a significant evolution for the federation.

Now, it’s the IOC’s turn, and its deliberations on Rule 50 cannot be limited to what American athletes might do in Tokyo, because an even bigger target is coming just seven months later.

Johnson was right: “it just takes time to see yourself in that, and to understand like where your placement is.” The time is almost here for the IOC to make some difficult decisions on how to accommodate expressions of athlete attitudes, potentially by U.S. athletes about their superpower home – which will host the 2028 Olympic Games – and by the U.S. and others about the actions of another superpower as it plays host to the 2022 Winter Games.

Rich Perelman

Editor

(Thanks to sharp-eyed reader Derrick Salisbury, noting that Mitt Romney helmed the 2002 OWG organizing committee, not 2022; now corrected. Thanks!)

You can receive our exclusive TSX Report by e-mail by clicking here. You can also refer a friend by clicking here, and can donate here to keep this site going.

For our 649-event International Sports Calendar for 2021 and beyond, by date and by sport, click here!