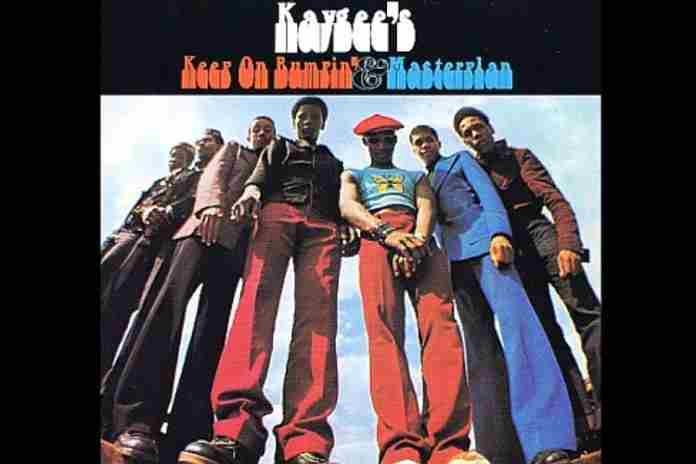

With the coronavirus keeping everyone apart these days, it seems impossible that – at one time – the most popular dance in America was The Bump, extolled by groups such as The Kay-Gees with their 1974 smash, Keep on Bumpin’.

The dance, the style, the bell bottoms are all long gone, but the tune could be re-recorded for track & field meets in Kenya and elsewhere under a new title, Keep on Dopin’.

While the postponement of the Tokyo Olympic Games to 2021 and the resulting fallout has been all the news for the past month, the parade of doping penalties for Kenyan athletes announced by the Athletics Integrity Unit has continued without end. So far this year alone:

● Jan 10: Wilson Kipsang: whereabouts failure

● Jan 14: Alfred Kipketer: whereabouts failure

● Feb 14: Peter Kwemoi: doping

● Feb 25: Kenneth Kipkemoi: doping

● Mar 18: Mercy Jerotich Kibarus: doping

● Mar 27: Vincent Yator: doping

● Apr 10: Daniel Wanjiru: doping

That’s seven cases in 3 1/2 months – all distance runners – not to mention two provisional suspensions and 14 decisions – 16 total – against Kenyan distance athletes in 2019. And these are not minor players.

Already suspended are Asbel Kiprop, the 2008 Olympic 1,500 m champ; Sarah Chepchirchir, the 2017 Tokyo Marathon winner and Jemima Sumgong, the 2016 Olympic marathon gold medalist. In this year’s class are former world marathon record holder Kipsang, 2018 Rotterdam Marathon winner Kipkemoi and Wanjiru, the 2017 London Marathon winner.

In all, there are 57 Kenyans listed on the AIU’s “Global List of Ineligible Persons” as of 30 March 2020 – you can add Wanjiru to bring the total to 58 – but they are hardly the worst offender. Russia leads the pack with 91, of course:

(1) 91, Russia

(2) 57, Kenya

(3) 48, India

(4) 34, Morocco

(5) 33, Turkey

(6) 32, China

(7) 29, Ukraine

(8) 26, Italy

The U.S. has 17 persons listed, including two coaches.

USA Weightlifting chief executive Phil Andrews (GBR) contrasted the sanctions protocol for weightlifting and track & field on Twitter back on 4 April after the International Weightlifting Federation banned Malaysia and Thailand from participating in the 2020 Tokyo Games:

“A correct and fair sanction handed to Thailand and Malaysia, the @iwfnet policy of national sanctions for multiple offences is tough but fair and reasonable especially with independent panel. I point out in our sport, Kenya’s long issues in Athletics would have been sanctioned.”

Further, TheGuardian.com (GBR) reported on a Leeds Beckett study of 301 athletes and 154 coaches, in Great Britain and the U.S., that found potential whistleblowers not sure of where to turn to report possible infractions.

Said lead researcher Dr. Kelsey Erickson (GBR): “In recent years we have seen a huge increase in the number of reporting mechanisms available for athletes and coaches to blow the whistle,. Yet while we found they often want to come forward, they often don’t know who to voice their concerns to, and they don’t necessarily trust action will be taken.”

The weightlifting policy against doping (2019 edition) includes penalties against those committing doping violations, but also against member federations. Three or more violations of the anti-doping policy “by Athletes or other Persons affiliated to the Member Federations” within a calendar year requires payment of a fine and the IWF’s Independent Disciplinary Panel may “impose a Suspension on the Member Federation of a period of up to (4) years.”

Further:

“If any Member Federation or its affiliated Athletes, other Persons or officials, by reason of conduct connected or associated with doping or anti-doping rule violations, brings the sport of weightlifting into disrepute, the Independent Panel shall impose any penalty upon the Member Federation that it considers just and proper in all the circumstances.”

This includes bans of up to four years as well, plus fines.

Isn’t it time that more federations start looking at these kinds of tiered sanctions programs for anti-doping violations? This puts pressure not just on the individual athlete to comply with the anti-doping regulations, but holds every athlete – and coach, agent, trainer and physician – responsible to all other athletes in their country not to be part of a doping regime that could get the federation banned.

Weightlifting’s situation is extreme and the sport was very nearly eliminated from the Paris 2024 Games because of its ridiculous doping history. But should individual sports like track and swimming be looking to reduce the number of qualifiers for Olympic or World Championships events if the number of sanctions is above a certain level, either in a specific year, or on a rolling average of, say, the three prior years?

Yes.

World Athletics (formerly the IAAF) has already taken a tough stance against Russia, essentially eliminating the country from competing in the 2016 Rio Games and then allowing only a carefully-vetted group of athletes to compete in its World Championships since then – 19 in 2017 and 29 in 2019 – owing to its egregious doping program from 2011-15 that is still yielding sanctions today.

But then the Russian federation tried to cover up a whereabouts violation for 2018 World Indoor Champion Danil Lysenko and the reinstatement process came to an abrupt end. In fact, the World Athletics Council issued a report in March noting that even these suspensions “have apparently been insufficient to prompt the required change in culture and behaviour in Russian athletics.”

So now the number of Russian athletes who can be entered in the Tokyo Games is limited to 10, assuming they pass whatever new criteria the World Athletics Doping Review Board comes up with.

For Russia’s part, a new set of senior officials at the federation has apologized for past transgressions – a first for RusAF – and promises to do better in the future. An important part of that is a national educational program against doping and a strict separation from those with past violations. On 5 April, a TASS story explained:

“Under the criteria, candidates to Russian track and field teams cannot be athletes who have violated anti-doping rules after November 18, 2015, with the exception of those [already] suspended for life. A team cannot admit an athlete suspected of anti-doping violations or under investigation. A candidate cannot work with a coach who has been disqualified for violating the anti-doping rules after November 19, 2015.”

But last Thursday, the Court of Arbitration for Sport “upheld an appeal from the Russian Anti-Doping Agency (RUSADA) and issued a four-year suspension against Russian track and field coach Andrei Yeremenko for his attempt to bribe a doping-control officer in 2017.” Yeremenko tried to get officials at the Russian national championships to allow 100 m hurdler Yulia Maluyeva to skip her post-event doping test because “she was ill” and apparently offered a bribe.

And Russia is still squirming to get out from under harsh penalties – four years of sanctions – handed out by the World Anti-Doping Agency, at the Court of Arbitration for Sport, with hearings possibly to be held in July. But on 10 April, new Russian sports minister Oleg Matytsin asked “we’re living in completely different conditions and this crisis which has been created, including the crisis in relationships, should probably come to an end, turn a new page and understand that the main thing right now is to be together.”

He offered to host events in Russia that have had to be abandoned elsewhere, and asked for “respect for the rights of the countries which are among the main actors on the international arena. Russia has always been, is and will remain that sort of partner.”

The answer to this has to be no, and WADA’s authority to hand out such sanctions must be confirmed in order for its credibility as a deterrent force to be maintained. In this light, WADA asked for the hearings on the Russian sanctions to be public, but it was the Russians who said no.

In track & field at least, the Athletics Integrity Unit has been pushing hard and the list of those on suspension is publicly available, in detail. It’s now time to put every national federation – in every sport – on the scoreboard to see if they can continue competing, or if their participation has to be reduced due to doping.

Otherwise, it’s time for find Ronald Bell from The Kay-Gees, author of “Keep on Bumpin’” and commission a revision for a new decade of doping.

Rich Perelman

Editor

You can receive our exclusive TSX Report by e-mail by clicking here. You can also refer a friend by clicking here.