(★ Friends: Thank you! Your 57 donations since mid-June have covered our half-yearly server and support costs, and starting to help with the next bill. If you would like to help, please donate here. Your interest and support are the reasons this site continues. ★)

It is today quite fashionable to wring one’s hands, shake the head and declare that these are dark times for our country, for the world and for this group or that.

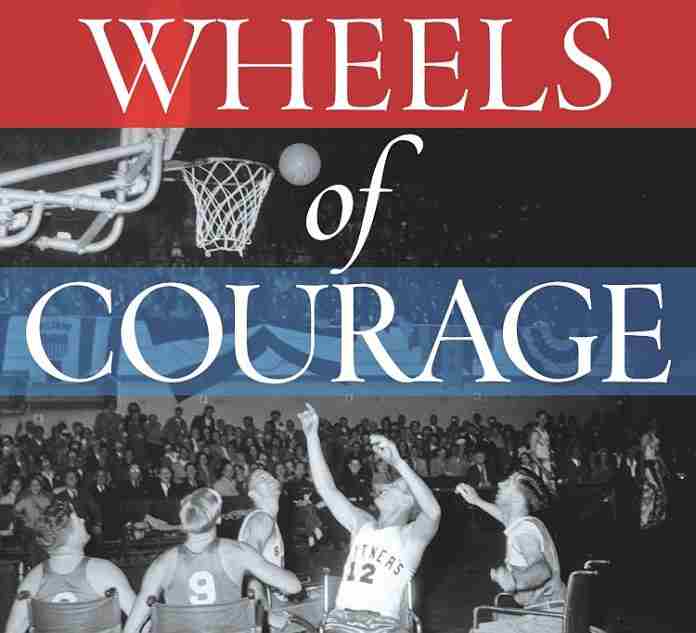

The soon-to-be released Wheels of Courage: How Paralyzed Veterans from World War II Invented Wheelchair Sport, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired Nation explains that individuals can change their – and our – future for the better, aided by the inevitable march of technology and the goodwill of people who are willing to help.

In expanding an article originally written for Los Angeles Magazine, Los Angeles-based author David Davis uncovered the astonishing story of how World War II veterans overcame devastating injuries that had doomed their World War I predecessors to death less than three decades earlier. We are introduced early to three of them:

● Johnny Winterholler, a 1939 honorable-mention All-American in football at the University of Wyoming, who was taken prisoner by the Japanese in the capture of the Philippines in 1941, eventually suffering paralysis of both legs due to maltreatment as a prisoner of war.

● Stan Den Adel of Corte Madera, California was shot and paralyzed in combat on the German-Austrian border a week before the end of fighting in Europe in May of 1945.

● Gene Fesenmeyer of Shambaugh, Iowa was on Okinawa in late May of 1945 when he was hit by a sniper’s bullet and lost the use of his legs.

For centuries, severe spinal injuries were “certain death and are ‘an ailment not to be treated.’” In World War I, victims of paralysis of the lower body and legs – “paraplegia” in medical terms – had died up to 90% of the time within one year following injury. But major advances such as the discovery of penicillin in 1928, sulfa tablets to restrict the growth of bacteria and revolutionary methods of collecting, maintaining and transporting blood and plasma to the front lines started saving lives in the 1940s.

Some 2,500 paralyzed veterans survived the war. Davis notes, however, “They were, at once, medical marvels and medical enigmas.” What to do with them now?

A new set of heroes emerge in this post-victory setting, including Dr. Ernest Bors of Hammond General Hospital of Staten Island, New York, who fled Czechoslovakia to escape Nazi oppression in 1940, and Dr. Howard Rusk from the Jefferson Barracks Hospital outside St. Louis, who convinced new U.S. Veterans Administration head Gen. Omar Bradley that rehabilitation was just as important as surgery: “We have to treat the whole man. And we also had to teach his friends and family how to accept him and help him in his new condition.”

The Veterans Administration established seven spinal-cord injury treatment centers across the nation, with Bors heading the new Birmingham General Hospital in Van Nuys, California; two additional naval hospitals were also designated for specialized care.

Den Adel was transferred to Birmingham General in November 1945 and saw similarly-paralyzed vets playing a simplified form of volleyball – with a lowered net – outdoors in the huge, wooden wheelchairs typical of the time, that had the main wheel in the front and small, stabilizing wheels in the back:

“When one of them accidentally steered his wheelchair into a wall, the others lambasted the poor soul: ‘Hey, Crip, do you have a license to drive that thing?’

“Den Adel couldn’t help laughing. Being together with others who were facing the same disability, all of them figuring out how to accommodate and assimilate their altered condition, was enormously therapeutic. ‘Every day somebody did something we didn’t know could be done from a wheelchair,’ he later wrote. ‘We shared our experiences with each other, speeding up the whole rehab process.’”

At the same time, there was a strong push to support veterans who had come home with varying difficulties, not only with treatment, but with jobs. News media were strongly supportive, as the times and trials of 16,000,000 U.S. veterans impacted every community in the nation.

Oldsmobile started offering cars with special hand controls to allow paraplegics to drive. Everest & Jennings, a Los Angeles firm, now offered a lightweight, foldable wheelchair made of chromed steel, vastly improving mobility.

In 1946, Birmingham Hospital’s assistant athletic director, Bob Rynearson, started offering basketball to the veterans, with some modest rule changes: two wheel pushes before dribbling, passing or shooting, 20 seconds to advance the ball past half-court and six seconds in the lane. Although the hospital’s gym was cramped, the vets quickly showed interest in the game, a highly competitive spirit and no trouble with getting back in action after a spill (often caused by a hard foul).

This was all in less than a year following V-J Day. While excruciating slow from the inside, and amazingly fast from the outside, Davis does a well-paced job of running the camera of your mind through the progress from shock to sorrow to exercise to competition to a future life.

On 25 November 1946, Rynearson had his “team” face off against a team of doctors from the hospital, who used borrowed wheelchairs. The vets won easily, 16-6, in what is considered the first wheelchair contest.

Then they started playing other, non-disabled teams in wheelchair games at the Pan-Pacific and Shrine Auditoriums in Los Angeles, and at the Long Beach Auditorium, with growing fan attendance and media interest.

At the same time, vets at Cushing General Hospital in Framingham, Massachusetts, were experimenting with their own brand of basketball. Their rules allowed racing downcourt without dribbling or passing, and even slight touches of chairs were called as fouls. On 5 December 1946, they played in a preliminary game in the Boston Garden against the Boston Celtics, prior to the Celtics-Detroit Falcons game in the new Basketball Association of America. Cushing won easily, 18-2.

Fesenmeyer and Winterholler were both recovering at the Naval Hospital at Corona (California), when it began offering wheelchair basketball, using Rynearson’s rules and methods from Birmingham. Inevitably, the two sides met in February 1947 in Corona, with Birmingham’s “Flying Wheels” defeating the “Rolling Devils,” 21-6, in the first match between organized wheelchair teams.

Playing with Winterholler in the line-up two months later, the Devils won the rematch, 41-10.

Now the Rolling Devils began making road trips, playing non-disabled teams in wheelchairs, including a 38-16 win over the semi-pro Oakland Bittners before 8,000 at the Oakland Auditorium, in a game sponsored by the Oakland Tribune. The net proceeds, as always, went to veterans’ relief funds.

Newspaper and newsreel coverage made the wheelchair game a national sensation. Teams sprung up at veterans’ hospitals everywhere, especially in the New York, an area already crazy for basketball. Halloran Hospital on Staten Island became the primary challengers to Cushing General from Massachusetts.

Out west, the active-duty Corona hospital facility required that the recovering, but discharged, vets go elsewhere, but Birmingham’s V.A. hospital team was still playing. A barnstrorming tour was arranged, but when the V.A. would not allow it, the players checked out of the hospital and boarded a plane. Fundraising was led by L.A. Herald-Express columnist John Old, with help from sportscaster Bob Kelley, star singer Bing Crosby and a young public-relations man named Tex Schramm, who went on to greater heights with the Dallas Cowboys of the NFL.

Wins in Kansas City, Chicago and Buffalo led to a February 1948 match-up of west vs. east in Framingham, as Cushing General – the “Clippers” – routed Birmingham, 18-7, using their “eastern” rules in what was hyped as the “world wheelchair basketball championship.”

There were more games in New York, in Richmond and Washington, D.C., which also included lobbying Congress for more benefits for veterans, and then more games before returning home.

A few days later, on 10 March 1948, some 15,561 fans filled Madison Square Garden in New York to see a doubleheader of Halloran General vs. Cushing General, won by Halloran, 20-11, prior to St. Louis’s 82-73 win over the Knicks in Basketball Assn. of America action. Wrote Davis:

“When the game started, the chatter in the stands gave way to uneasy, muted murmuring. Halloran’s Jack Gerhardt was speeding around the court like racecar driver Mauri Rose cornering at the Indianapolis 500 when he collided with another player and spilled out of his chair. Matrons gasped and dabbed at their eyes with handkerchiefs; crusty sportswriters complained that the smoke from their Lucky Strikes was causing them to tear up. But after Gerhardt muscled his body back into his chair and demanded the ball, and after the Cushing crew brayed their displeasure at the officials – ‘Whatsamatta, ref, can’t you hear either?’ – the mood inside the arena relaxed, and the fans began to cheer and whistle as if they were witnessing a miracle.”

All of this in two-and-a-half years after the end of the war. But as the veterans continued to recover, they yearned for the same things as their fellow brothers-in-arms: marriage, family, a home of their own and a career.

Slowly, the story of wheelchair basketball grew beyond the purview of WWII veterans, especially after the Korean War, and companies like Bulova and Pan American Airways saw promotional benefits from sponsoring teams, as well as from hiring wheelchair-bound veterans. Davis chronicles the long road from the novelty and wonder of injured veterans putting on a show on the basketball floor to the formation of the National Wheelchair Basketball Association to passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act in the 1990s.

And the rest of the world was not asleep. What started as a wheelchair archery tournament named the Stoke Mandeville Games, held concurrently with the 1948 Olympic Games in London, eventually became the Paralympic Games, now formally attached to the Olympic Movement and which will host 4,400 athletes in 22 sports in Tokyo in 2021.

Davis includes rich details of the support for these veterans, especially in the late 1940s, from Hollywood stars to fawning news coverage, as well as the eventual in-fighting between these pioneer teams and the expansion of disabled sport within the U.S. and worldwide. The pace of the book slows in the final third, as the V.A. narrowed its support for sports that took patients out of their hospitals for more than two days in 1950, the same year as the Birmingham Hospital was closed (it’s now the site of Birmingham High School, with the appropriate nickname of the Patriots.)

Published by Center Street, a division of Hachette Book Group, the book will launch officially on 25 August, which was to have been the date of the opening of the 2020 Paralympic Games in Tokyo. But you don’t have to wait a year to enjoy the story of how veterans and those who believed in them changed their world and ours for the better: you can pre-order it here.

Rich Perelman

Editor

You can receive our exclusive TSX Report by e-mail by clicking here. You can also refer a friend by clicking here.