In the continuing tumult over the future of the Tokyo Games and the worldwide struggle with the coronavirus, the 10-year anniversary of the passing of one of the most important man in the history of world sport was only slightly noticed.

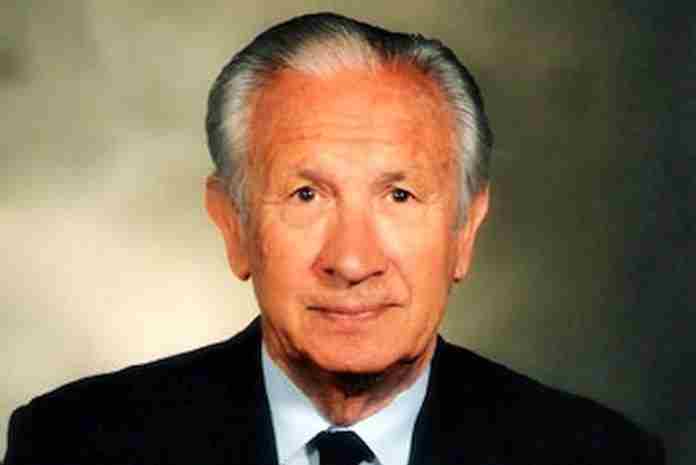

Spain’s Juan Antonio Samaranch, who led the International Olympic Committee from 1980 to 2001, changed it and the world sport movement forever. He passed away on 21 April 2010 at age 89, in his native Barcelona.

Much of Samaranch’s life was involved with Olympic sport and he was Spain’s chef de mission for the 1956 Winter Games, 1960 Olympic Games and 1964 Olympic Games. He was elected to the IOC in 1966 and became a member of the Executive Board in 1970.

In the meantime, he was involved in local and regional governmental posts in Francoist Spain. He was the head of the governing council in Catalonia in 1977 when Spain re-opened diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and Samaranch was appointed as Spain’s ambassador to Moscow (and to Mongolia).

From 1977 to 1980, Samaranch was posted to Moscow and continued his involvement in sport, not only as an IOC member, but with a front-row seat to the workings of the Warsaw Pact countries in the sports arena. He watched the impact of the U.S.-led boycott on the 1980 Games in Moscow and was elected by the IOC as its seventh president on 16 July 1980 – three days before the opening ceremony – and took office on 3 August, at the close of the Moscow Games. The backing of the IOC members from the Warsaw Pact countries was an important element in his election.

He took over in the middle of a mess.

Not only had their been boycotts in Montreal in 1976 and Moscow in 1980, but the IOC itself was on thin financial ground, with the next Games coming in Los Angeles in 1984 … with – for the first time – no governmental guarantees to cover any potential deficits.

Where his predecessor, Ireland’s Lord Killanin, had been a largely absentee president, Samaranch moved to Lausanne and placed him personally at the center of the Olympic Movement at the IOC’s modest offices at the Chateau de Vidy. The staff numbered about 30 and was led by the former French Olympic swimmer Monique Berlioux, herself a sizable authority figure in the Olympic Movement.

But it became quickly clear that Samaranch was in charge, and over the succeeded years led a stunning change in the IOC’s fortunes, making the organization so popular, rich and successful than it descended into corruption. Some of the major milestones:

● 1980: Samaranch took over an IOC of 83 members, all men. He brought the first women into the IOC in 1983 and at the time he left in 2001, the IOC had 127 members, including 11 women, including two on the Executive Board.

● 1981: He created the first IOC Athletes’ Commission, led by Finnish sailor Peter Tallberg and including German fencer Thomas Bach and British middle-distance star Sebastian Coe.

● 1984: In response to the Soviet boycott of the Los Angeles Games, Samaranch worked closely with the L.A. Olympic Organizing Committee to recruit nations to attend the Games. A record total of 140 paraded into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for the opening ceremony.

● 1984: Shortly after the Los Angeles Games, the Court of Arbitration for Sport was created, providing a venue for the resolution of trans-national disputes in the sports world. Until this body was activated, obtaining jurisdiction over any of the International Federations and even the IOC had been difficult.

● 1985: Following the dazzling financial model pioneered by the Los Angeles Games, Samaranch created The Olympic Programme, the first worldwide Olympic sponsorship program that offers marketers not only local rights to the Games, but rights across (almost) all of the National Olympic Committees worldwide.

● 1986: The IOC moved into a new, modern headquarters, adjacent to the Chateau de Vidy. The Chateau had originally been leased in 1968 to house a staff of 12. The new headquarters held more than 100 staff and has expanded continuously to today.

In the same year, the IOC voted to stagger the staging of the Winter and Olympic Games, so that a Games was held every two years.

● 1992: The IOC took over the negotiation and sale of all television rights to the Games, starting with the 1992 Winter Games in Albertville (FRA) and Barcelona (ESP). More than any other area, this secured the IOC’s financial future.

● 1993: Samaranch had championed the creation of a permanent Olympic Museum, which finally opened in 1993, next to the IOC’s new office building

● 1996: With the IOC’s blessing, International Sports Broadcasting was formed in Spain, and contracted as the host broadcaster for the Olympic Games, taking the production effort away from Olympic organizing committees and national broadcasters. The IOC formed its own operation, Olympic Broadcast Services, in 2001.

● 1999: The World Anti-Doping Agency was founded in Montreal (CAN) to answer the needs for a coordinated, worldwide effort against doping.

With significant money coming into the IOC, Samaranch also expanded the Olympic Solidarity program in 1981 to give assistance to National Olympic Committees, and distribute a big share of the IOC’s television revenues to the International Federations.

In 1992, the Barcelona Games was hailed as one of the best ever and, held in Samaranch’s hometown, has become a paradigm for the use of the Games as part of a civic renovation effort.

Against all of this expansion, however, was a loss of integrity of some IOC members. In 1998, Swiss member (and Federation Internationale de Ski chief) Marc Hodler complained that IOC members had received bribes in regard to the vote for the 2002 Winter Games, won by Salt Lake City. That resulted in a major scandal, with the expulsion of 10 IOC members (and sanctions against 10 more), a prohibition – still maintained – against IOC members visiting candidate cities and Samaranch’s appearance before a U.S. House Commerce subcommittee in December of 1999.

In some ways, the IOC has still not recovered. Samaranch has further been pilloried by those who rail against his participation in Spain’s Fascist regime (it was a one-party state until 1975 and was in transition to a constitutional monarchy during Samaranch’s tenure in Moscow). But the IOC of the 21st Century is very much Samaranch’s handiwork.

So where does he rank among the list of IOC Presidents? For me, he’s no. 2 of eight:

(1) Pierre de Coubertin (FRA: president from 1896-1925)

He formed the IOC and created the revival of the Games in the 1890s and his continuous lobbying and promotion of the event helped make it a major international spectacle by 1906. His ceaseless leadership led to a continuous improvement in the quality of the Games, the revival of the Olympic Movement in the aftermath of World War I, the introduction of the Olympic Winter Games in 1924 and even the award of what turned out to be a revolutionary Games in Los Angeles for 1932. De Coubertin is the reason the Olympic Games exist today.

(2) Juan Antonio Samaranch (ESP: 1980-2001), as noted above.

(3) Sigfrid Edstrom (SWE: 1942-52)

Belgian Henri de Baillet-Latour died in 1942 as the world was engulfed in the second World War and the Olympic Movement teetered on extinction. But Edstrom, who had been an IOC member since 1921, had participated in the organization of the 1912 Stockholm Games and was one of the founders of the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF), had the advantage of living in neutral Sweden and kept up a correspondence with the IOC membership. This led to a 1945 Executive Board meeting and the first Session in six years in 1946. He oversaw the revival of the Games in London in 1948 and an excellent Games in Finland in 1952, at age 82. An important and under-appreciated link in keeping the Olympic Games alive.

(4) Jacques Rogge (BEL: 2001-2013)

The Belgian physician who succeeded Samaranch as president, he had significant issues in the aftermath of the Olympic bid scandal in Salt Lake City. Rogge was a steady hand and introduced a more democratic, more relaxed style to the IOC in which differing opinions could be heard. With IOC revenues increasing significantly during his two terms, he insisted on building a large reserve so that even a cancellation of an Olympic Games (!) would not shut the IOC down. Under his watch, he nurtured the troubled Athens Games over the finish line in 2004, the IOC controversially selected Beijing to host the 2008 Olympic Games and sent the Games to South America for the first time with the selection of Rio de Janeiro in 2009. Rogge also championed the creation of the Youth Olympic Games, first held in 2010; the event has been criticized as unnecessary and wasteful, but has morphed under Thomas Bach into a living laboratory for future Olympic programming concepts.

(5) Henri de Baillet-Latour (BEL: 1925-42)

How do you follow Pierre de Coubertin? An IOC member since 1903, Baillet-Latour had been a key in the success of the 1920 Antwerp Games and ensured that there would be no letdown in the work of the IOC after the retirement of its founder. He worked energetically with the Los Angeles organizers in 1932 to help ensure the success of that Games during the Great Depression and then did what he could to hold the Movement together through the infamous 1936 Games in Berlin (which had been awarded to Germany in 1931, before the ascension to power of Adolf Hitler). It has been repeatedly reported that Baillet-Latour told Hitler not to congratulate event winners in the Olympiastadion, unless he would congratulate all of them. But he was more concerned that the Games take place than to press the Nazis to change their racial attitudes, a stance which later IOC chiefs have been repeated since.

(6) Demetrios Vikelas (GRE: 1894-96)

Vikelas was the first elected head of the IOC, as the initial rules required its president must be from the country where the next Games will be held. He convinced the in-formation IOC that the first modern Games must be held in Athens in 1896, instead of in Paris in 1900. Thus, he was the first IOC chief and enthusiastically promoted the concept in his native country, receiving enough governmental support to allow the event to happen and start the modern Games on its way.

(7) Avery Brundage (USA: 1952-72)

Perhaps the most controversial of the IOC Presidents, Brundage came into the IOC as a “younger man” at age 64 in 1952. He became an authoritarian figure within international sport, especially insistent on maintaining the amateur standing of athletes and only reluctantly accepting the Games as a worldwide television spectacle. In the post-World War II environment, he was immediately challenged by determining what to do about the re-entry of Germany into the Games, allowing West Germany into the 1952 Games and then forcing a combined – “unified” – team of West and East Germans in the 1956, 1960 and 1964 Games. The two nations competed separately beginning in 1968. Similar problems arose with China refusing to compete as long as Taiwan was allowed, and South Africa was not allowed to compete due to its racist policies from 1964 on. Brundage was adamantly against any Olympic athlete making money in sports, even as “state amateurs” in the Warsaw Pact countries emerged. And faced with the Palestinian terrorism at Munich in 1972, he insisted at the memorial service that “the Games must go on.” Out of touch with many elements of the world-sport movement, especially from American athletes, his retirement after the Munich Games was widely cheered.

(8) Lord Killanin (IRL: 1972-80)

Taking over for Brundage was going to be difficult, but Killanin had no luck at all. He was quickly faced with the withdrawal of Denver as the host city for the 1976 Winter Games and Innsbruck was named instead. African nations boycotted the Montreal Games in 1976 and the organizing committee ran up a C$1 billion deficit that was not paid off for another 30 years. In the aftermath, only one city – Los Angeles – bid for the 1984 Games and even then without any governmental financial guarantees. And then there was the U.S.-led boycott of the Moscow Games, after which Killanin relinquished the IOC presidency with many speculating that a privately-financed Los Angeles Games would never even happen.

What about Bach, the current IOC chief? He has not completed even one term as President as yet, so he is not ranked. Let’s leave that for 2021, after the end of his first term.

And your rankings? Send in your top three (and any comments) by Sunday (10th) and we’ll compile the results … if anyone is interested.

Rich Perelman

Editor

You can receive our exclusive TSX Report by e-mail by clicking here. You can also refer a friend by clicking here.