Being old does have some benefits. One of them – for as long as it lasts – is memory.

When the International Swimming League (ISL) held an athlete’s conference in London (GBR) last week, followed by a self-congratulatory Web posting, there was an echo from long ago.

Yes, 46 years ago.

In London, ISL founder Konstantin Grigorishin – the Ukrainian head of the Energy Standard Group – said on the ISL Web site that “We can co-exist with FINA and respect each other if they understand that their role is that of a regulator of rules not people. And they need to understand that athletes deserve their fair share of all revenues they generate as the stars of swimming.”

And the InsideTheGames Web site quoted Grigorshin as saying the “day of the sports governing body is coming to an end.” Both ISL and a group of three athletes – Americans Tom Shields and Michael Andrew and Hungary’s Katinka Hosszu – have filed suit against FINA for restraint of trade, with the athletes aiming to be certified as a class-action plaintiff.

During the conference, a program of ISL meets was announced for 2019, between August and the end of the year, with a minimum of $5.3 million in prize money, based on a $15 million budget (35.3%). But the announcement also noted that there is, at present, “no sponsors or revenue.” There was also no schedule of meets or locations other than semifinals and finals in Las Vegas (USA) next December, no television broadcast agreements and no roster of swimmers who have signed up. There was a list of swimmers who attended the meeting to at least show interest.

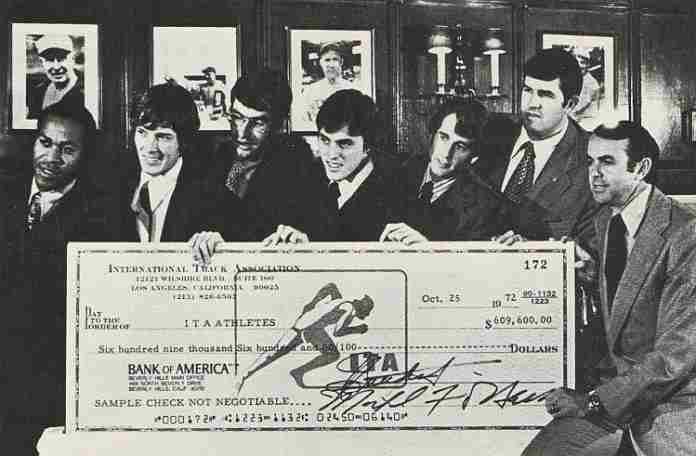

Long-time followers of track & field remember this scenario very well. Shortly after the 1972 Olympic Games, a group called the International Track Association (ITA) announced that it would be staging a series of meets beginning in 1973 featuring many of the top stars in the sport at the time. Current or former world-record holders from the U.S. such as Jim Ryun (mile), Lee Evans (400 m), Bob Seagren (pole vault) and Randy Matson (shot put) and Olympic champions including Kip Keino of Kenya were all signed to compete for the ITA.

And they did. The first meet was held indoors on 3 March 1973 in Pocatello, Idaho (USA) before 10,480 spectators and saw indoor world-best performances from Warren Edmonson in the 100 m (10.2), Evans in the 600 m (1:17.7) and John Radetich in the high jump (7-4 3/4). Each of these would have been world records except that they were professionals, which was against the Inter-national Olympic Committee and International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) rules at the time.

There were 51 ITA meets from 1973-76 and 34 world-best performances, including Brian Oldfield’s unforgettable 75-0 (22.86 m) shot put in El Paso in 1975, a mark not surpassed until 1987.

But the circuit failed. Although the cumulative attendance was around 500,000 – an average of just less 10,000 per meet, which would be excellent today – it did not generate enough interest from television and investors to continue. And the inability to sign new talent from the 1976 Olympic Games meant that no new stars would be competing in the meets and the ITA’s profile faded quickly.

The ITA made a lasting impact, however, and helped usher in the era of openly-professional athletes in track, swimming and all other Olympic sports. Although those ITA athletes who tried to regain their Olympic eligibility could not do so, or were finally allowed back only in 1980 – well after their prime – their contribution to the fully-professional athletes of today is not to be forgotten.

For those swimmers who are hot to see ISL succeed – and get paid more than they are now – the ITA should be a cautionary tale. The ITA had experienced organizers and new ideas which are commonplace now; the graphics line which is shown on television to compare the pace of swimmers to the world record is simply an update of the revolutionary ITA idea to use lights ringing the track that showed the world-record pace of each race as it was going on.

In its own post on its conference in London, ISL’s founder was clear that the issues which doomed the ITA as an entity after four years of operations remain in place today:

Grigorishin pointed out that swimmers have far bigger challenges long-term, compared to overcoming FINA pressure, in raising their earning power in a competitive trillion-dollar global sports industry. “You are in the entertainment business, show business. And eventually you are competing against other entertainment properties, the likes of Netflix, for the short attention span of the global audience. That is your biggest challenge. Another challenge is technology and the exponential growth of e-sports. Swimming needs to catch up with the technological evolution to stay relevant with the young audience. This all requires swimming to find new exciting formats that engage far more people of all ages beyond its existing core fans.”

The ITA had a lot going for it, but had to compete with the amateur side of the sport, including the Olympic Games, and could not survive. The International Swimming League has filed its lawsuits against FINA, alleging restraint of trade, but Grigorishin’s comments point to the real challenge.

Is swimming a relevant sport for spectators in 2019? ISL’s project supposes that it is, but it offers no answers or details, only the founder’s open questions. Grigorishin will get his opportunity to succeed – FINA is not going to suspend the swimmers – but will he? And for how long?

Rich Perelman

Editor