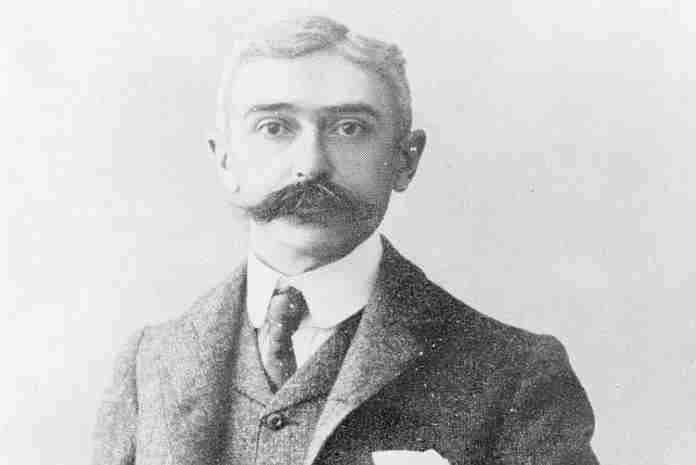

On Monday, the International Olympic Committee gleefully welcomed the donation of the original manuscript of Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s 1892 speech that called for the revival of the ancient Olympic Games.

The 14-page text, handwritten by de Coubertin, was purchased at auction for $8.8 million – the largest amount ever paid for sports memorabilia – by Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov. As president of the Federation Internationale de Escrime, he has been personally underwriting the expenses of the governing body of fencing for several years, and now purchased and donated the document from which the birth of the modern Olympic Games can be traced.

So was de Coubertin’s speech a rousing promotion for an Olympic revival?

Nope. In fact, when actually read, it’s no wonder that what the 29-year-old Frenchman had hoped was a “call to action” fell completely flat.

In 1994, then-IOC chief Juan Antonio Samaranch directed that de Coubertin’s manifesto be re-printed in French and translated into English in a thin volume called “Le Manifeste Olympique” and published under the auspices of the IOC.

De Coubertin’s lecture, given as part of the fifth anniversary program of the Union des Sociétés française de Sport athlétiques (USFSA) in November 1892 at Le Sorbonne in Paris, actually dealt with physical fitness, with the Olympic Games mentioned only as the final two works of the address. Some highlights:

● “The century which began so tragically and which is ending today in a troubled and uncertain peace follows one of great intellectual activity and veritable physical inertia.”

● “All [sports in France] was dead, and when the Directoire, steeped in memories of Ancient Greece, wanted to set up on the Champ de Mars in Paris something akin to an Olympic Games, one indispensable element was missing: competitors.”

● “I said that German gymnastics was energetic in its movements. On that condition alone, it is effective. Now, for this energy to be maintained, gymnasts must perpetually be under a warlike influence. The idea of war must never cease to inspire them.”

● [In England] “if boxers were seen to be killing each other here and there, or a rowing competition was held n the Thames, it as between professionals to give spectators the pleasure of losing their money on exaggeratedly high bets. There was nothing sporting or athletic about it.”

● “English athletics, Gentlemen, began only recently, and already it is taking over the world. … sixty years have sufficed for this prodigious transformation. … A certain philosophical glow surrounded them: reminders of Greece, respect for the stoic traditions and a fairly clear idea of the services that athletics could render the modern were now slow in drawing attention to them. When the movement gained ground, they were furiously and angrily attacked. But their work was already under the protection of youth.”

● “A special press has been set up to cover the interests of the athletic world. … On the days of major [sports] meetings business stops, offices empty, and there is a truce like in Ancient Greece to applaud the young people as they pass.”

● “Finally, how could one forget fencing? Is it not our national sport, in which only Italy can rival us for supremacy, the one which allows us to savor honorably the joy of fighting, the greatest after the joy of living?”

De Coubertin went on to note that an important step had been made within France in 1887, when competitions were expanded to include matches between sports clubs, and not merely within a specific club. He attached great importance to this, and led directly to his conclusion.

Saying “the role of a prophet is one full of danger,” he nevertheless exhorted his audience:

“It is clear that the telegraph, railways, the telephone, the passionate research in science, congresses and exhibitions have done more for peace than any treaty or diplomatic convention. Well, I hope that athletics will do even more. Those who have seen 30,000 people running through the rain to attend a football match will not think that I am exaggerating. Let us export rowers, runners and fencers; this is the free trade of the future, and the day that it is introduced into the everyday existence of old Europe, the cause of peace will receive new and powerful support.

“That is enough to encourage me to think now about the second part of my programme. I hope that you will help me as you have helped me thus far and that, with you, I shall be able to continue and realize, on a basis appropriate to the conditions of modern life, this grandiose and beneficent work: the re-establishment of the Olympic Games.”

The speech drew applause, but almost no action; that’s hardly surprising given the absence of any argument that the revival of the Olympic Games would solve his perceived crisis of physical fitness in France, or would be a catalyst in the expansion of competitions.

But in reading de Coubertin’s remarks, one can see his genius, especially in the marketing of the idea of “English athletics” which had developed rapidly since the 1860s. Why not have competitions on an inter-national level instead of on a purely intra-national basis as a way to promote exercise and healthier living … without the goal of training for war!

This was the true breakthrough in this speech, and de Coubertin – with help from others – persevered and finally saw the formation of the International Olympic Committee in 1894.

The first modern Games was held in 1896 in Athens, and de Coubertin retired from the IOC in 1925, after the second Games held in his beloved Paris in 1924. He came back into public view in the 1930s and in a radio address in 1935, he looked back on what he had helped create, but instead of a worldwide fitness movement, he found he had created a cult:

“The ancient as well as the modern Olympic Games have one most important feature in common: They are a religion. When working on his body with the help of physical education and sport – like the sculpturer at a statue – the athlete in antiquity honored the gods. By doing the same today, the modern athlete honors his homeland, his race, and his flag.

“I think, I was right, therefore, when reconstituting the Olympic Games to have connected them with a religious feeling from the beginning. It is transformed and even elevated by internationalism and democracy — the features of our time — but basically it is still the same as in antiquity when it encouraged the young Greek to employ all of their strength for the highest triumph at the feet of the statue of Zeus . . . The religious idea of sport, the religio athletae, has entered very slowly into the consciousness of the athlete, and many of them act accordingly only by instinct.”

De Coubertin died two years later, in 1937, having seen his concept brutalized by Nazi Germany for its own purposes. But despite two stoppages for war, the Olympic Games has survived and grown. What de Coubertin started has morphed far beyond his original idea, and with the coming inclusion of public-participation events at the third Paris Games in 2024, the IOC is finally fulfilling its founder’s dream … 132 years later.

Rich Perelman

Editor

You can receive our exclusive TSX Report by e-mail by clicking here. You can also refer a friend by clicking here.