The newest tool for promoting athletes in Olympic sports was pioneered 72 years ago in San Bruno, California.

World rankings.

If you follow USA Wrestling’s impossibly comprehensive coverage of their sport at TheMat.com, you know that the first men’s Freestyle Rankings for 2019 appeared on Tuesday, continuing its ranking program that started at least as far back as 2001.

Wrestling’s international federation, United World Wrestling, adopted a world ranking program as part of its revision of the sport – in order to stay in the Olympic Games – in February 2018.

Archery has world rankings. So does badminton, modern pentathlon and table tennis. The world rankings in fencing and judo are so deeply ingrained in their competition platforms that they are posted with each athlete’s name in the entry lists for World Cup and Grand Prix competitions. And, of course, all of the team sports have them.

These are all fairly new. Professional tennis was an early adopter of the concept, beginning back in 1973.

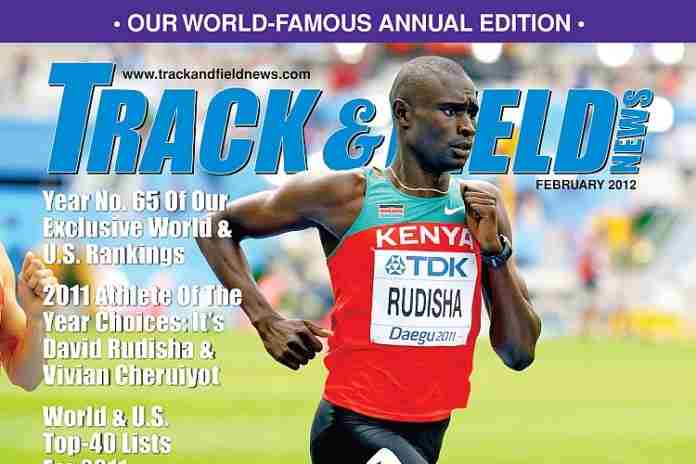

But the idea came from a tiny, start-up magazine covering track & field back in 1947. The T&FN Web site explains:

“The first-ever Rankings, for the ‘47 season (men only), were the brainchild of T&FN cofounder Cordner Nelson. The next year he handed the task off to stat legends R.L. Quercetani & Don Potts, who shepherded the project for the next three decades.

“In ’56, Czechoslovakia’s Jan Popper began parallel women’s Rankings; these were folded into the T&FN family in the early ’80s.”

Nelson’s idea was not to establish a rolling series of rankings that would establish who was the “best” at any moment in time. Instead, the concept was to grade out the best athletes in a single year, one against another.

That’s a little different than the intent of the rankings from most of today’s federations, who carry rankings from year to year. Most are based on a computer-generated points system which pre-assigns values to specific competitions, usually based on their level. A victory in the Olympic Games or World Championships means a lot more than at a Pan American Championship or a World Cup, and so on down the line.

But that’s not how T&FN’s World Rankings work. And the magazine’s criteria are better. As has been the case since the beginning, the T&FN World Rankings are based on three simple criteria, in descending order of importance:

1. Honors won.

2. Head-to-head records with other athletes.

3. Sequence of marks.

As the January 1964 edition of T&FN further explained, “Ranking is not based on the best mark for each man, nor are the athletes listed in the order in which the compilers believe they would finish in an idealized contest.”

That’s clear. It’s not at all clear what the rankings posted by international federations mean, other than that someone has the most points at a given time.

The beauty of the T&FN rankings concept is that it rewards not only winning (or placing high), but who you beat, in what meet and when. For someone to set a world record early in the season is noteworthy, but if they faded into obscurity as the season went on and then performed miserably in the championship meets, their ranking would be low (or none).

For an athlete who built on success during the season, rose to greatness as the competition got tougher and reached their peak at the height of the season, they receive the highest standing.

That’s hard to program into a computer, but a very human approach to who did best in a given year or season. And that’s why it’s better, then and now.

It took more than 70 years, but the governing body of track & field, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) – finally got around to adopting the idea last year and introducing its own ranking system in 2019. It has some serious flaws – we noted them previously – but will be used, in part, for entry into the 2020 Olympic Games and for the World Championships beginning in 2021.

But the IAAF approach is once again computer-driven and fails to recognize the importance of specific competitions which may be critical in a specific year, but not in other years.

Wouldn’t it be better for a federation ranking system to be based on a two-layer approach, using a computer-generated points system for a first listing, then reviewed by actual experts in the sport? That would certainly make for more interest, since it’s hard to argue with a computer, but more interesting (and fun) to argue with “experts.”

(There is also another approach, which is used by the Federation Internationale de Ski, which compiles World Cup standings on an annual basis only, but has a ranking system to determine who has priority in race draws, the infamous “World Cup Start List” rankings.)

Strangely, the term “world rankings” means something entirely different in swimming. For the aquatics federation, FINA, the term “world rankings” simply means the best times in each year, one per swimmer per event. This is clearly objective, but hardly exciting. In a time when there are new promotional energies in swimming, it might behoove the FINA to check into how an actual merit-ranking system might work and attach annual awards (and money) to such a program.

Gymnastics has nothing like this at all, but this makes some sense in that many of the top gymnasts appear so rarely during the year. A “season” which includes just a handful of performances is hard to rank, but it’s worth noting that T&FN faces the same issues with ranking marathoners annually and still makes that work.

Known as the Bible of the Sport almost since its beginning in the 1940s, T&FN carries on today and its annual merit rankings are a far more precise tool to measure achievement that the IAAF’s multi-million-dollar project, or those of other federations.

At their best, T&FN’s World Rankings are both a reference point and the starting line for heated arguments. Isn’t that what the federations really want?

Rich Perelman

Editor