/With one year to go before the Paris 2024 Games, it’s a pleasure to present this guest column by George Hirthler, who has been working in the Olympic world since 1989 when he was engaged by Billy Payne as the lead writer on Atlanta’s bid for the 1996 Olympic Games. Since then he has served as a writer/producer on ten international Olympic bid campaigns, including the winning bids of Beijing 2008, Vancouver 2010 and LA 2028. In 2016, Hirthler published The Idealist, a fictionalized biography of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games, and is currently writing and producing two feature-length documentaries on Atlanta 1996 and Pierre de Coubertin respectively. The essay that follows, which will be part of the book, L’aventure Olympique, to be published this fall by L’Harmattan in France, draws parallels between the French and American roles in founding the Olympic Movement and carrying it toward the future. His opinions are, of course, his own alone./

It is a fact of modern life that the Olympic Games are the world’s greatest single celebration of humanity. Far more than just a festival, they carry deeply embedded and meaningful cultural content to every society on earth. While some have claimed the Games have outlived their 19th century origins and are irrelevant today, recent history suggests the opposite is true: the Olympic Games and the global sporting movement that sustains them seem to be more relevant than ever.

As Paris 2024 begins to crowd the headlines with its milestone statement of gender equality – the first Games to achieve a 50/50 male/female balance in the 130-year history of the modern movement – the currency of the social values being expressed through the Games could hardly be more timely. At the same time, a worldwide debate about the inclusion of athletes from aggressor nations Russia and Belarus has raged in the foreground of sports and political news for more than a year, putting the Olympic Movement at the center of one of the most pressing ideological arguments of the era: the rights of the individual in the context of bad behavior by his or her national government.

Two years ago in 2021, Tokyo 2020 – the first Olympics postponed in the modern era – turned the Games into a global laboratory about whether humanity could continue to compete in the face of a worldwide pandemic. Although it faced arguably the greatest existential threat in its history, the Olympic Movement overcame all obstacles and objections and managed to gather 11,420 athletes from 206 national teams for 339 events in a bubble of venues in Japan and answered that question with a resounding “Yes, we can.” Undoubtedly, that feat will one day be rendered by history as perhaps the greatest organizational achievement in the annals of event production, let alone the Games. And one year ago, the Olympic Movement had to protect its autonomy by facing down immense political pressure from human rights advocates and governments seeking to diminish China’s standing while it sought to give 2,871 winter athletes on 91 teams the opportunity of a lifetime in another bubble at the Beijing Winter Games.

Despite the scope and size of the Games, these recent challenges have helped turn the movement into a nimble organization with greater adaptability than ever. It is far from the moribund old-school, out-of-touch institution it is often accused of being. Under Thomas Bach’s leadership, its resiliency has emerged as its greatest strength. Elected as the ninth IOC president in Buenos Aires in September 2013, Bach spent his first year mounting a unanimously-approved set of reforms entitled Agenda 2020: approximately 50 measures designed to increase the movement’s social relevance in the days, weeks, months and years between Games and, at the same time, ensure that all operations, logistics and organizational efforts evolved into models of social responsibility and sustainability for society at large. Bach wanted to make sure the International Olympic Committee, which had labored under one of the world’s most infamous reputations and credibility gaps for years, rose in public standing to a level of integrity commensurate with the world’s admiration for the Games.

In 2017, during the third summer of his presidency at the IOC Session in Lima, Peru, Bach revealed an imaginative range that suggested his Agenda 2020 reforms would carry more depth than the dismissive window-dressing labels many Olympic reporters had pinned on them. In a move that hearkened back to one of Pierre de Coubertin’s final major decisions, Bach led the IOC to award the next two Olympic Games to two of the world’s leading cities, and Paris and Los Angeles walked away from Peru as the simultaneously-elected hosts of the 2024 and 2028 Olympic Games.

Bach knew that in 1921, Coubertin had sent his colleagues in the IOC a letter announcing that he had decided to retire in 1925 and asked the IOC membership for one final favor, a favor he knew they would not deny him: To award the 1924 Olympic Games to Paris, the city of his birth, and the 1928 Games to Amsterdam, which had submitted a masterful plan for hosting the Games. That year at the IOC Session in Lausanne, Coubertin’s wishes were confirmed, and the future of the Olympic Movement looked secure as its founder prepared to retire.

Just as Coubertin’s double award reached three years beyond his presidency to Amsterdam, so will Bach’s, whose presidency is scheduled to end in 2025, three years before LA 2028. It is striking to note that like Coubertin, Bach will preside over his last Olympic Games in Paris – 100 years later – a fact that demarcates a series of parallels between their presidencies. Without reading too much into these parallels, there is another striking similarity between the presidencies of the second and ninth presidents. Both men had to guide the Olympic Movement through a crisis that threatened its very existence – World War I and the global coronavirus pandemic – and both managed to bring the Games, assuming Paris 2024 lives up to its lofty expectations, to new heights with a bright future ahead.

It is interesting to note that Bach has become something of a Coubertin aficionado during his presidency, studying the founder’s life and weaving a series of pertinent quotes from the Baron’s vast oeuvre into the speeches he has given and continues to give. He is on record as saying his favorite Coubertin quote depicts the Olympic Games as “a pilgrimage to the past and an act of faith in the future.” ¹

Both sides of that equation ring with spiritual sentiment; a pilgrimage is often thought of as a religious journey and an act of faith is looking ahead in full belief. If we put Paris 2024 and LA 2028 in that framework, we can see the dimensions of Coubertin’s thinking at work. Since it will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the last summer Olympics it hosted, Paris will by necessity look back even as it astounds the world with innovations that may turn its Opening Ceremony along the Seine into something that evokes the spirituality Coubertin alluded to. And during the Closing Ceremony when Bach takes the Olympic flag from the Mayor of Paris and passes it to the Mayor of Los Angeles, an act of faith in the future will be completed.

The soaring idealism the world will witness in Paris 2024 and again in LA 2028 will express in new ways Coubertin’s visionary dream of uniting the world in friendship and peace through sport. And if the storytellers do their work properly – given the fact that we’re celebrating Coubertin’s legacy in the city of his birth – they will remind the world of the full power and promise of the philosophy of Olympism that sits at the heart of his legacy. At some point, the world will have to reckon with the full dimensions of Olympism, and recognize that what Coubertin wrote is true: “Olympism did not reappear within the context of modern civilization in order to play a local or temporary role. The mission entrusted to it is universal and timeless. It is ambitious. It requires all space and all time.”

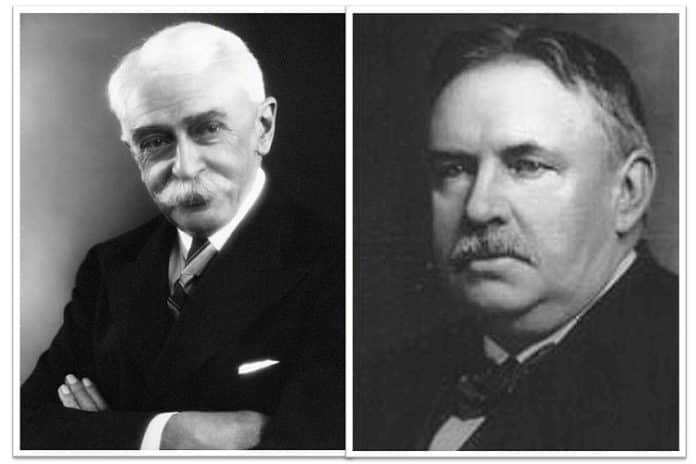

Yes, the Olympic Movement is ambitious. It has been on an inexorable path of expansion since its birth at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1894. It was there that a vision shaped primarily between Pierre de Coubertin and his remarkable American ally, William Milligan Sloane, the distinguished professor of history at Princeton University and head of its athletics committee, took root.

At its core, the modern Olympic Movement, which was born under the patronage of the peace movement, built its idealistic success on the sporting passions of the two nations Coubertin and Sloane represented, France and America, each of which had gone through a revolutionary transformation hardly a century before they met. While the model of competition Coubertin and Sloane embraced sprang from the playing fields of England, they each had a broader vision for the local and global purposes of sport. On the local level, they shared an educational vision for the value of sport in developing the whole human being. On the international level, they envisioned the possibilities of a competition growing to such stature and allure that it might influence the relationships between nations and contribute to building a better world focused on peace. At the heart of the Olympic Movement, they constructed a ladder of values that led from the personal to the universal, from human excellence, to mutual respect, to friendships formed on the field of play, to international understanding and ultimately to fostering the idea of world peace.

Sloane, who was twelve years older than Coubertin and widely recognized as a brilliant writer and historian well before the Games were born, added intellectual heft to the movement and helped define its most idealistic goals. In 1920, after the Antwerp Olympic Games, he wrote a perspective piece summarizing the work that he, Pierre and a handful of other true believers accomplished in launching the modern Olympic Games, clearly positioning their aim as that of peace:

“The movement for international conciliation has attained very important dimensions. Its goal is nothing short of international disarmament, chimerical as this vision may appear. Among the agencies to this end the work of the International Olympic Committee is likely to be of great importance, and the achievement of its first twenty-five years should not be overlooked by any who are lovers of mankind and have at heart the well-being of their fellows. The peaceful evolution of the newer civilization is not only fascinating to the imagination, but a definite, practical and possible process. The beginnings of things always contain the germ: life comes only from life. But the direction and amplitude of growth are not easily foreseen.” ²

His praise for the drive and achievements of his French friend and colleague could not have been greater. He always assigned the prime credit for the success of the Games to the man known as le rénovateur:

“… the lifelong devotion of M. de Coubertin, his tact, his ingenuity, his self-sacrifice in time and money, in short, the qualities of faith and merit, have been the chief reason for the solid establishment of the enterprise.” ³

From the outset, the success of the modern Olympic Games and their devotion to the highest aspirations and noblest ideals of humanity were rooted in a French-American partnership. As we stand on the threshold of the Games of the XXXIII Olympiad in Paris, looking ahead to the Games of XXXIV Olympiad in Los Angeles, it is once again those two champions of modern sport and Olympism that are carrying the hopes and dreams of this inexorable movement toward the future.

References:

1. Coubertin, Pierre, The Ceremonies, Olympic Review (1910): an article about the religious atmosphere found in ancient Olympia and Coubertin’s desire to recapture that atmosphere in modern times.

2. Sloane, William Milligan, Modern Olympic Games in The Official Report of the American Olympic Committee on the 1920 Antwerp Olympic Games, (1920), p. 71.

3. Sloane, William Milligan, The Olympic Idea: Its Origins, Foundation and Progress, The Century Magazine (1912), p. 414.